Bruce Wolpe, University of Sydney

Seven months after Donald Trump was inaugurated for a second term as US president, we are facing the most important moment in Australia’s foreign policy since the Iraq war. Australia needs to have a national conversation on the future of its alliance with the United States.

The alliance was on the line with Trump’s tariff decisions on August 1. The consensus was Australia dodged a bullet, and life goes on.

But this was no flesh wound. By dictating and unilaterally imposing the terms of trade between the US and Australia – affirming the “reciprocal tariffs” of 10% imposed on Australia, plus the tariffs of 50% on both steel and aluminium – Trump has trashed the historic US–Australia Free Trade Agreement.

Trump has not provided a good answer to the question of what he is doing to one of the US’s strongest and most consistent allies. And there is more to come. The president will also place a tariff on US imports of Australian pharmaceuticals.

There is also far more to come on the future of the US–Australia alliance.

Media have been full of opinions on what the relationship between the two countries ought to look like. These interventions have assayed the crucial importance of Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese meeting personally with Trump; whether Washington was rattled by Albanese’s visit to China, whether Australia should “fortify northern Australia into an allied military stronghold for the region”; and whether the relationship is being mismanaged.

The best model for this conversation would be the economic roundtable Treasurer Jim Chalmers will host in Canberra this month. Its purpose, Albanese said, is to “build the broadest possible base of support for further economic reform”.

Why not apply the same process to the future of our foreign policy and alliance with the US?

A similar roundtable, convened by the foreign minister, and bringing together the smartest and most experienced people from across the political and foreign policy spectrum to discuss all these issues, would provide the best and most sincere guidance for the country.

A new reality

There are three bedrock truths that are unimpeachably clear since Trump reassumed power in the US.

First, Australia has not changed; the US has changed. Albanese and his government has not changed its posture towards the US. Trump has profoundly changed America’s posture towards Australia.

Second, the US is no longer the leader of the free world, because the free world is no longer following America. The democracies with which the US has been allied since the end of the second world war are no longer acting in concert with the US, but in reaction to what Trump is doing across the global landscape – from the Americas, to the Atlantic, Russia, the Middle East, China, the Indo-Pacific and Australia.

Third, Trump has destroyed the economic and trading architecture erected after the second world war to promote growth and prosperity. Nations engaging economically with the US are no longer trading partners but trading victims. The “deals” Trump boasts about are involuntary. Trump’s imposition of tariffs even on countries with a trade deficit with the US shows that his trade policy is at heart the unilateral exercise of US political power to force concessions to US domination.

What is under profound challenge today – 84 years after Prime Minister John Curtin turned to the US and 73 years after the ANZUS treaty came into effect – is whether the US under Trump is still aligned with the vision the two countries have shared for decades.

Australians have serious doubts about the relationship. The latest polling by Resolve Political Monitor documented “a strong desire for the country to assert more independence from the United States amid Donald Trump’s turbulent presidency”.

Fewer than 20% of Australian voters believe Trump’s election victory was good for Australia. Nearly half of voters believe it would be “a good thing” for Australia to act more independently of the US. Pew Research reported in July that only 35% of Australians believe the US is a top ally.

Trump is driving away US allies. Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney said after winning office, “Our old relationship with the United States, a relationship based on steadily increasing integration, is over.”

When the leaders of Japan and South Korea received Trump’s insulting letters of demarche on trade, they each said the correspondence was “deeply regrettable”, with Japan’s prime minister adding, “extremely disrespectful”.

Trump has also precipitated a trade war with India. How effective can the Quad – established by the US, Japan, India and Australia to serve as a counterweight to China – be if three of its four members are victims of Trump’s tariffs?

Australia has also broken with Trump on recognition of Palestine – issues of the highest importance to the president. Moreover, if the terms of whatever Trump is conjuring up with Putin to end the war with Ukraine are unacceptable to Ukraine and Europe, and Trump sides with Putin, a further sharp break by Australia with Trump is likely.

The “soft power” wielded by Australia is also involved here. From the UN’s inception, Australia has supported the architecture required to help secure peace, security, stability and the health and welfare of all peoples. But Trump has now withdrawn the US from UNESCO, the World Health Organization, the World Trade Organization, the Paris climate accords, the UN Human Rights Commission and others. He has terminated the USAID programs that delivered crucial health care and crisis relief. Medical studies project that millions of people will die as a result die in the coming years.

Australia uses that architecture to help change the world for the better. Trump is making that work much harder.

Time to talk

Trump is repealing all US programs that combat global warming – the most important environmental issue of our times and the number-one existential security issue for Asia-Pacific nations. Australia shares their urgency.

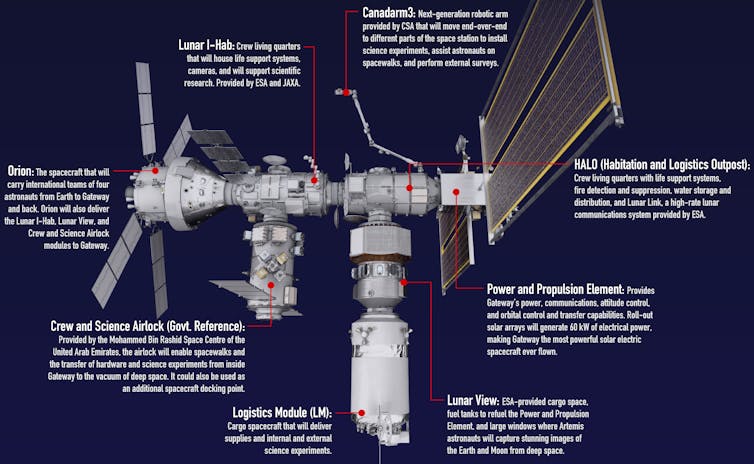

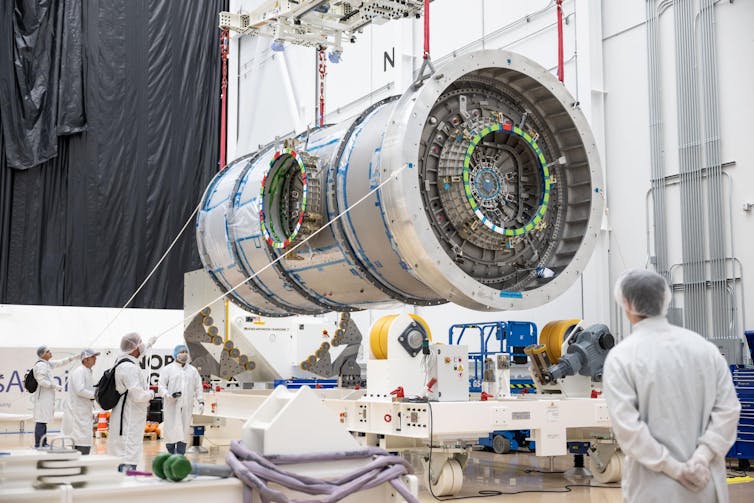

Since Trump’s inauguration, AUKUS has consistently been viewed as a bellwether for the relationship. Australia’s need for a modern submarine fleet is an existential issue of the country’s defence capability.

Will Trump, during the Pentagon’s review of AUKUS, change its terms to be more favourable to the US? Is Australia spending enough on defence? Will the pace of submarine construction ensure Australia receives the subs in the 2030s? If not, are there better solutions than AUKUS?

But the most important question is the most known unknown. What does Trump want from China? Trump has never outlined his endgame with President Xi Jinping. Yes, of course, the trade deal of the century. But at what price, particularly with respect to Taiwan? What are the consequences of all the scenarios and what does Australia need to do to be prepared?

Trump is president and will continue to act with power and drama. Albanese will respond on behalf of Australia. That would be business as usual. But without the benefit of a considered national conversation about the future of the Australian–US alliance and what is in Australia’s national interest, the current state of play does not rise to the challenges posed by Trump to Australia.

US baseball legend Yogi Berra once said, “When you come to a fork in the road, take it.” That’s where we are. Let’s talk about it.![]()

![]()

Bruce Wolpe, Non-resident Senior Fellow, United States Study Centre, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.