Six journalists are among the dead in Ukraine, as world leaders scramble to prevent a greater international conflict.

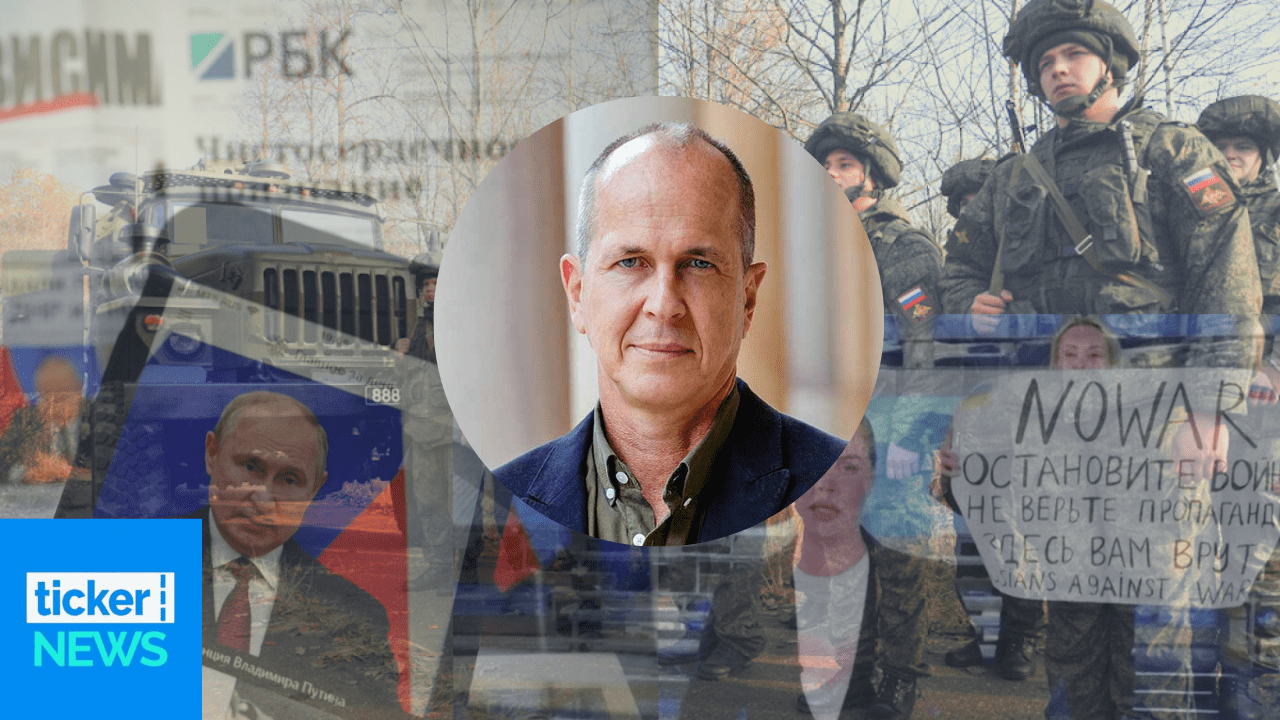

Ticker NEWS spoke exclusively with journalist Professor Peter Greste bout the importance of a free and diverse media during wartime periods.

Professor Peter Greste is an international journalist who has covered many wars, he told Ticker NEWS the current rhetoric from Moscow is “propaganda”.

Greste has covered a lot of wars in recent history, but he says its hard to think of any conflict that is “quite as morally unambiguous as this one.”

“The evidence that we’ve seen so far of Russian tactics, particularly in targeting civilian areas, seems just outrageous,” he told ticker’s Adrian Franklin,

“Some of the rhetoric some of the propaganda coming out of Moscow seems almost as horrific.”

Greste says we could be confronting the next international war, the next World War.

“I think we’re going to see a hardening of public opinion and and it’s going to be much more difficult for anybody to negotiate a settlement,” he says on the overall outlook of the war right now.

“I think we’re going much more likely to see a more aggressive and protracted conflict. This is not over anytime soon.”

War-time media reporting in a country criminalising independence

“It’s made it almost impossible for Russian journalists to operate independently and with integrity in Russia,” Greste says.

Russians have passed a law that criminalised what they describe as deliberately false information about the deployment of the military forces of the Russian Federation.

Now, they’re defining deliberately false information as any casualty figures.

Greste says this includes not using words like war or invasion. Instead, the Russians have described it as a special military operation, which is a euphemism. “This clearly is designed to try and minimise what the Russians are doing.”

“Increasingly, and perhaps troublingly, we’ve seen the Russian support for President Clinton, President Putin steadily increase. Now, I think he’s still in a rather precarious position,” he says.

“A lot of people, including myself, an idiot, initially said that the truth would would leak out, that the Russians would get access to more accurate information, that’s slowly start to understand the extent of the propaganda coming from Mosco,”

“But I think the effectiveness of their internal propaganda in their attempts to close down anything that might undermine that propaganda is really working. And in a way, I think this is going to make things more difficult for Russia to back down, not easier.”

Is journalism the most dangerous professions to be in right now?

Six journalists are among the dead in Ukraine, as world leaders scramble to prevent a greater international conflict.

At first glance, Greste says it seems like a deliberate target by Russians, however more investigation from organisations like Reporters Without Borders, CPJ, and the committee for the protection of journalists are underway.

“In per capita terms, this conflict is already one of the most dangerous since the Second World War for journalists in particular,”

Greste says

World leaders are being watched like a hawk

The stakes are colossally high, and if any world leader makes a misstep, then we could find ourselves in another world war, says Greste.

“And if we don’t confront Russia, if we don’t get more aggressive, then we run the risk of sending a message to Moscow that it’s okay to invade neighbouring states with impunity.”

The repercussions come at a high risk, Russia could send its troops over the border into places like Poland, and the Baltic states, Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia.

The award winning journalist says world leaders have to deal with the problem of working out a way of finding a path through this conflict, that gives Russia a means to withdraw without losing face.

He adds that there’s been a lot of criticism of Vladimir Putin.

“And that’s perfectly justified, given what we know of the way that he’s been conducting the war. But if he has no way to go without losing face, if he has no way of backing out without being seen amongst his own people to concede defeat, then he has nothing to lose,” he says.

News3 days ago

News3 days ago

News5 days ago

News5 days ago

Leaders3 days ago

Leaders3 days ago

Shows3 days ago

Shows3 days ago

News3 days ago

News3 days ago

Docos5 days ago

Docos5 days ago

Leaders4 days ago

Leaders4 days ago

Leaders4 days ago

Leaders4 days ago