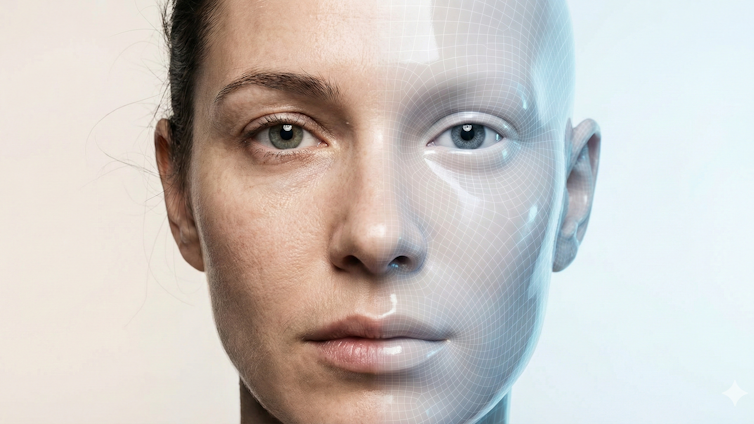

AI-generated image by Siwei Lyu using Google Gemini 3

Siwei Lyu, University at Buffalo

Over the course of 2025, deepfakes improved dramatically. AI-generated faces, voices and full-body performances that mimic real people increased in quality far beyond what even many experts expected would be the case just a few years ago. They were also increasingly used to deceive people.

For many everyday scenarios — especially low-resolution video calls and media shared on social media platforms — their realism is now high enough to reliably fool nonexpert viewers. In practical terms, synthetic media have become indistinguishable from authentic recordings for ordinary people and, in some cases, even for institutions.

And this surge is not limited to quality. The volume of deepfakes has grown explosively: Cybersecurity firm DeepStrike estimates an increase from roughly 500,000 online deepfakes in 2023 to about 8 million in 2025, with annual growth nearing 900%.

I’m a computer scientist who researches deepfakes and other synthetic media. From my vantage point, I see that the situation is likely to get worse in 2026 as deepfakes become synthetic performers capable of reacting to people in real time.

Dramatic improvements

Several technical shifts underlie this dramatic escalation. First, video realism made a significant leap thanks to video generation models designed specifically to maintain temporal consistency. These models produce videos that have coherent motion, consistent identities of the people portrayed, and content that makes sense from one frame to the next. The models disentangle the information related to representing a person’s identity from the information about motion so that the same motion can be mapped to different identities, or the same identity can have multiple types of motions.

These models produce stable, coherent faces without the flicker, warping, or structural distortions around the eyes and jawline that once served as reliable forensic evidence of deepfakes.

Second, voice cloning has crossed what I would call the “indistinguishable threshold.” A few seconds of audio now suffice to generate a convincing clone – complete with natural intonation, rhythm, emphasis, emotion, pauses, and breathing noise. This capability is already fueling large-scale fraud. Some major retailers report receiving over 1,000 AI-generated scam calls per day. The perceptual tells that once gave away synthetic voices have largely disappeared.

Third, consumer tools have pushed the technical barrier almost to zero. Upgrades from OpenAI’s Sora 2 and Google’s Veo 3, and a wave of startups mean that anyone can describe an idea, let a large language model such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT or Google’s Gemini draft a script, and generate polished audio-visual media in minutes. AI agents can automate the entire process. The capacity to generate coherent, storyline-driven deepfakes at a large scale has effectively been democratized.

This combination of surging quantity and personas that are nearly indistinguishable from real humans creates serious challenges for detecting deepfakes, especially in a media environment where people’s attention is fragmented and content moves faster than it can be verified. There has already been real-world harm – from misinformation to targeted harassment and financial scams – enabled by deepfakes that spread before people have a chance to realize what’s happening.

The future is real-time

Looking forward, the trajectory for next year is clear: Deepfakes are moving toward real-time synthesis that can produce videos that closely resemble the nuances of a human’s appearance, making it easier for them to evade detection systems. The frontier is shifting from static visual realism to temporal and behavioral coherence: models that generate live or near-live content rather than pre-rendered clips.

Identity modeling is converging into unified systems that capture not just how a person looks, but how they move, sound, and speak across contexts. The result goes beyond “this resembles person X,” to “this behaves like person X over time.” I expect entire video-call participants to be synthesized in real time; interactive AI-driven actors whose faces, voices and mannerisms adapt instantly to a prompt; and scammers deploying responsive avatars rather than fixed videos.

As these capabilities mature, the perceptual gap between synthetic and authentic human media will continue to narrow. The meaningful line of defense will shift away from human judgment. Instead, it will depend on infrastructure-level protections. These include secure provenance, such as media signed cryptographically, and AI content tools that use the Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity specifications. It will also depend on multimodal forensic tools such as my lab’s Deepfake-o-Meter.

Simply looking harder at pixels will no longer be adequate.![]()

![]()

Siwei Lyu, Professor of Computer Science and Engineering; Director, UB Media Forensic Lab, University at Buffalo

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.