Berna Akcali Gur, Queen Mary University of London

The Lunar Gateway is planned space station that will orbit the Moon. It is part of the Nasa‑led Artemis programme. Artemis aims to return humans to the Moon, establishing a sustainable presence there for scientific and commercial purposes, and eventually reach Mars.

However, the modular space station now faces delays, cost concerns and potential US funding cuts. This raises a fundamental question: is an orbiting space station necessary to achieve lunar objectives, including scientific ones?

The president’s proposed 2026 budget for Nasa sought to cancel Gateway. Ultimately, push back from within the Senate led to continued funding for the lunar outpost. But debate continues among policymakers as to its value and necessity within the Artemis programme.

Cancelling Gateway would also raise deeper questions about the future of US commitment to international cooperation within Artemis. It would therefore risk eroding US influence over global partnerships that will define the future of deep space exploration.

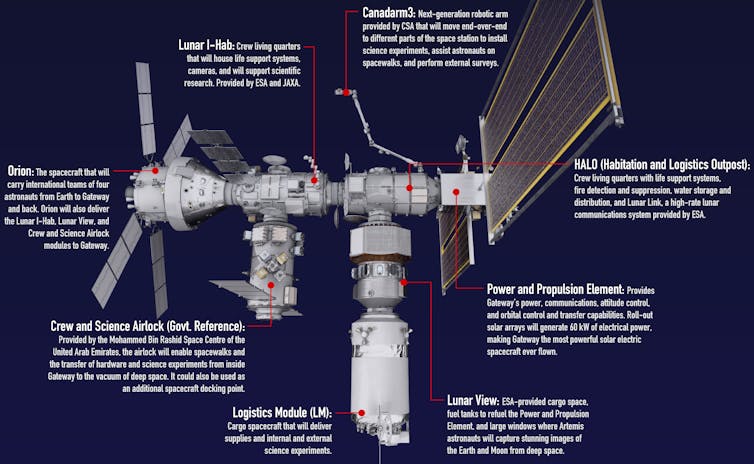

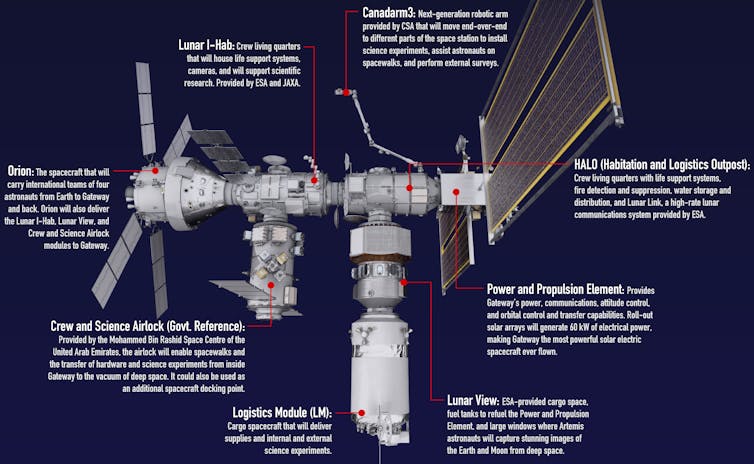

Gateway was designed to support these ambitions by acting as a staging point for crewed and robotic missions (such as lunar rovers), as a platform for scientific research and as a testbed for technologies crucial to landing humans on Mars.

It is a multinational endeavour. Nasa is joined by four international partners, the Canadian Space Agency, the European Space Agency (Esa), the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency and the United Arab Emirates’ Mohammed Bin Rashid Space Centre.

Nasa

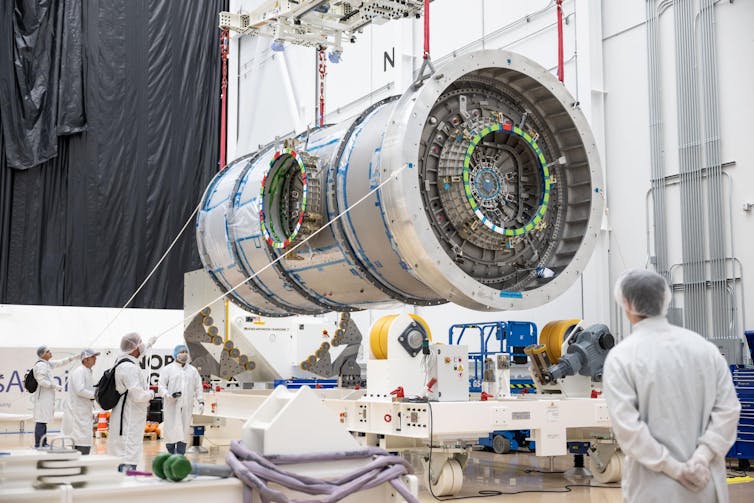

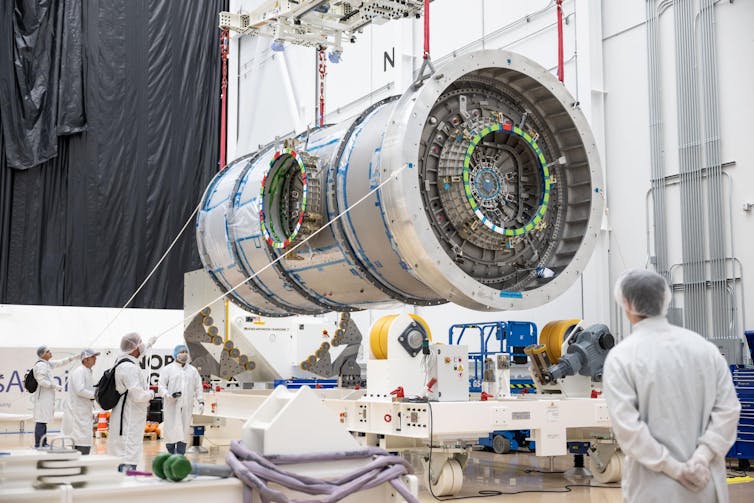

Most components contributed by these partners have already been produced and delivered to the US for integration and testing. But the project has been beset by rising costs and persistent debates over its value.

If cancelled, the US abandonment of the most multinational component of the Artemis programme, at a time when trust in such alliances is under unprecedented strain, could be far reaching.

It will be assembled module by module, with each partner contributing components and with the possibility of additional partners joining over time.

Strategic aims

Gateway reflects a broader strategic aim of Artemis, to pursue lunar exploration through partnerships with industry and other nations, helping spread the financial cost – rather than as a sole US venture. This is particularly important amid intensifying competition – primarily with China.

China and Russia are pursuing their own multinational lunar project, a surface base called the International Lunar Research Station. Gateway could act as an important counterweight, helping reinforce US leadership at the Moon.

In its quarter-century of operation, the ISS has hosted more than 290 people from 26 countries, alongside its five international partners, including Russia. More than 4,000 experiments have been conducted in this unique laboratory.

In 2030, the ISS is due to be succeeded by separate private and national space stations in low Earth orbit. As such, Lunar Gateway could repeat the strategic, stabilising role among different nations that the ISS has played for decades.

However, it is essential to examine carefully whether Gateway’s strategic value is truly matched by its operational and financial feasibility.

It could be argued that the rest of the Artemis programme is not dependant on the lunar space station, making its rationales increasingly difficult to defend.

Some critics focus on technical issues, others say the Gateway’s original purpose has faded, while others argue that lunar missions can proceed without an orbital outpost.

Sustainable exploration

Supporters counter that the Lunar Gateway offers a critical platform for testing technology in deep space, enabling sustainable lunar exploration, fostering international cooperation and laying the groundwork for a long term human presence and economy at the Moon. The debate now centres on whether there are more effective ways to achieve these goals.

Despite uncertainties, commercial and national partners remain dedicated to delivering their commitments. Esa is supplying the International Habitation Module (IHAB) alongside refuelling and communications systems. Canada is building Gateway’s robotic arm, Canadarm3, the UAE is producing an airlock module and Japan is contributing life support systems and habitation components.

Nasa / Josh Valcarcel

US company Northrop Grumman is responsible for developing the Habitat and Logistics Outpost (Halo), and American firm Maxar is to build the power and propulsion element (PPE). A substantial portion of this hardware has already been delivered and is undergoing integration and testing.

If the Gateway project ends, the most responsible path forward to avoid discouraging future contributors to Artemis projects would be to establish a clear plan to repurpose the hardware for other missions.

Cancellation without such a strategy risks creating a vacuum that rival coalitions, could exploit. But it could also open the door to new alternatives, potentially including one led by Esa.

Esa has reaffirmed its commitment to Gateway even if the US ultimately reconsiders its own role. For emerging space nations, access to such an outpost would help develop their capabilities in exploration. That access translates directly into geopolitical influence.

Space endeavours are expensive, risky and often difficult to justify to the public. Yet sustainable exploration beyond Earth’s orbit will require a long-term, collaborative approach rather than a series of isolated missions.

If the Gateway no longer makes technical or operational sense for the US, its benefits could still be achieved through another project.

This could be located on the lunar surface, integrated into a Mars mission or could take an entirely new form. But if the US dismisses Gateway’s value as a long term outpost without ensuring that its broader benefits are preserved, it risks missing an opportunity that will shape its long term influence in international trust, leadership and the future shape of space cooperation.![]()

![]()

Berna Akcali Gur, Lecturer in Outer Space Law, Queen Mary University of London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.