Rod Sims, The University of Melbourne

Australia’s new emission reduction target of 62–70% by 2035 is meant to demonstrate we are doing our part to hold climate change well below 2°C.

The new target can just about do this if we hit the upper end of the range.

To get there, Climate Change and Energy Minister Chris Bowen today outlined new funding to help industry go clean and boost clean energy financing and clean fuels.

On top of our existing policies, these don’t look to be enough to trigger the step change needed. But there is a deeper problem. At present, the government’s approach is one of command and control. Canberra is deciding what goes ahead and what doesn’t. This approach is not only inefficient but has a very real limit – how far the public purse will stretch.

Far and away the best option to rapidly cut emissions is to once again price carbon. When it costs money to emit carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, markets start shifting huge amounts of money into clean alternatives. The funds raised can help strengthen the budget – and compensate consumers, who are currently not being compensated for current policy costs.

The question now is whether the government can shake off their memory of the political turmoil around the introduction of the last carbon price introduced in 2012 – especially given this turmoil had much to do with constant leadership changes.

Is this range the “sweet spot”?

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese described the long-anticipated 2035 target range as a “sweet spot”, while Minister Bowen said anything more ambitious than 70% was not achievable.

While this focus on achievability is commendable, it’s also unfortunately true that Australia’s remaining carbon budget is shrinking rapidly.

Globally, this budget represents the emissions that can still be emitted with a good chance of keeping warming under 2°C. Australia’s share is about 10 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent between 2013 and 2050, when we have pledged to hit net zero.

At present, our emissions are about 440 million tonnes a year, which would mean using up our budget by 2036 – well short of 2050. So we must accelerate emission reduction.

Some experts argue a lower target than just announced is appropriate, given policies aren’t in place to achieve more. But this is self-defeating – the focus must be on having the appropriate policies.

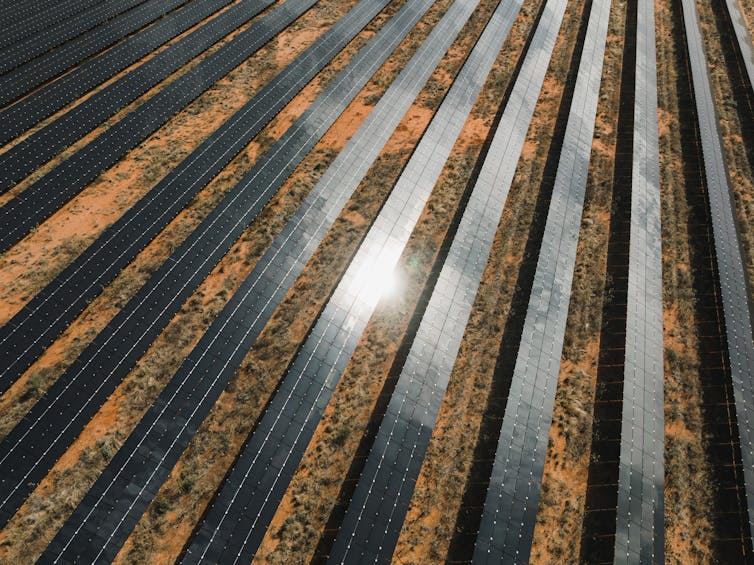

Abstract Aerial Art/Getty

Reaching this target requires better policies

Australia’s current suite of policies are leading to slow declines in emissions.

Unfortunately, the government’s new and existing policies don’t seem up to the task of meeting the 43% by 2030 target, let alone the new 62–70% cuts five years later.

To date, the government has heavily relied on two policies to bring emissions down. Both have flaws.

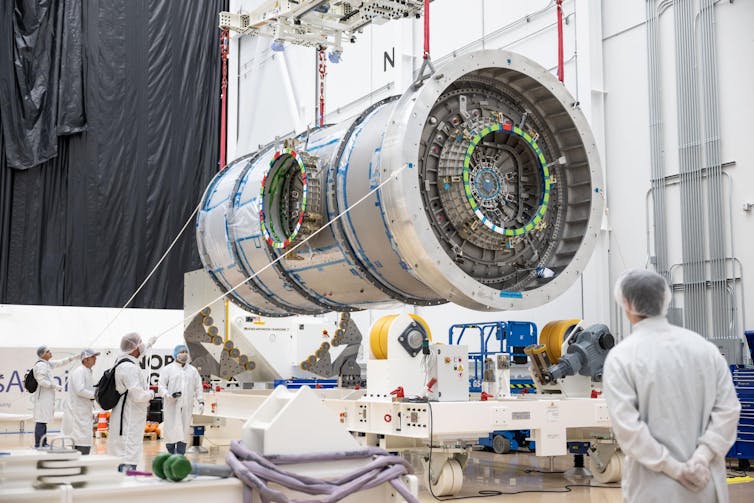

The first is the Capacity Investment Scheme, which underwrites renewable energy generation and storage projects. In the absence of a carbon price, the government needs to underwrite projects as there is no green premium to create incentives for market-led investment. The government, not the market, is deciding which clean energy projects proceed.

Underwriting new projects comes with a large contingent liability, as the Commonwealth budget is partly underwriting these projects. The scheme is proceeding more slowly than the government hoped.

The second is the Safeguard Mechanism, which requires major industrial emitters to progressively lower their emissions. The scheme covers less than 30% of the economy and applies to emissions intensity rather than overall emissions, meaning higher production can lead to higher emissions.

Today, the government announced A$5 billion to support large industrial facilities to make major investments in decarbonisation and energy efficiency, $1 billion for a clean fuel fund, $2 billion to accelerate renewable project rollout and additional funding for household decarbonisation and kerbside EV charging. As it stands, these don’t seem sufficient.

Outside the land use sector, Australia’s emissions have remained broadly flat since 2005. They haven’t risen sharply, but they have not declined. If the government restricts itself to small adjustments to existing policies, this is unlikely to change.

mikulas1/Getty

Time to look at a carbon price

It would be far simpler to reintroduce a carbon price.

For two years from June 2012, Australia had a carbon price. It worked. Markets funded lower-emission power sources over higher-emission ones. But the scheme became politically fraught and was repealed. Since then, pricing carbon has been seen as politically unviable.

This paralysis is unfortunate. We need to judge what is politically possible today, not what happened a decade ago. Notably, in 2021, the Morrison Coalition government released modelling showing a carbon price would be necessary to reach net zero.

With a carbon price off the table, the government is left with expensive and slow policies. Worse, it faces significant political risks if it fails to meet its own targets while increasing costs to consumers – without the revenue a carbon price could provide as compensation.

Much of the debate over carbon pricing is between supporters of climate action and those who oppose any action to reduce emissions. Those wanting climate action have been forced to fight on weaker ground defending inefficient measures. It’s counterproductive not to use the most efficient mechanism to reduce emissions.

Unlock the private sector – by pricing carbon

To make real headway towards cutting emissions, Australia needs to energise the private sector.

Here, too, the best way is to price carbon. This would mean fossil fuel producers and users would have to pay for the damage their products do. Without this incentive to reduce emissions, companies will not take action.

The fault lies with government. Having identified greenhouse emissions as a major and growing problem, successive governments have refused to take the obvious step to fix it: make pollution cost money.

In 2025, it’s very unlikely any private investor will build new fossil fuel generation, other than gas peaking plants to firm renewables. No investor will build extremely expensive and slow nuclear plants.

That means the electricity grid can only meet rising demand – particularly from the enormous growth in data centres – if we add much more renewable energy, firmed by storage or gas.

Over time, the budget would improve from the proceeds of the carbon price, and productivity would grow as Australia’s expensive and somewhat arbitrary methods of cutting emissions would no longer be needed.

A carbon price is needed now to underpin our electricity market, and so our economy, improve our budget position and productivity – and to meet or surpass new emission reduction targets.

2035 is just ten years away. If the government prices carbon, Australia could achieve very rapid reductions – potentially as high as 75%.![]()

![]()

Rod Sims, Enterprise Professor, Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.