Ticker Views

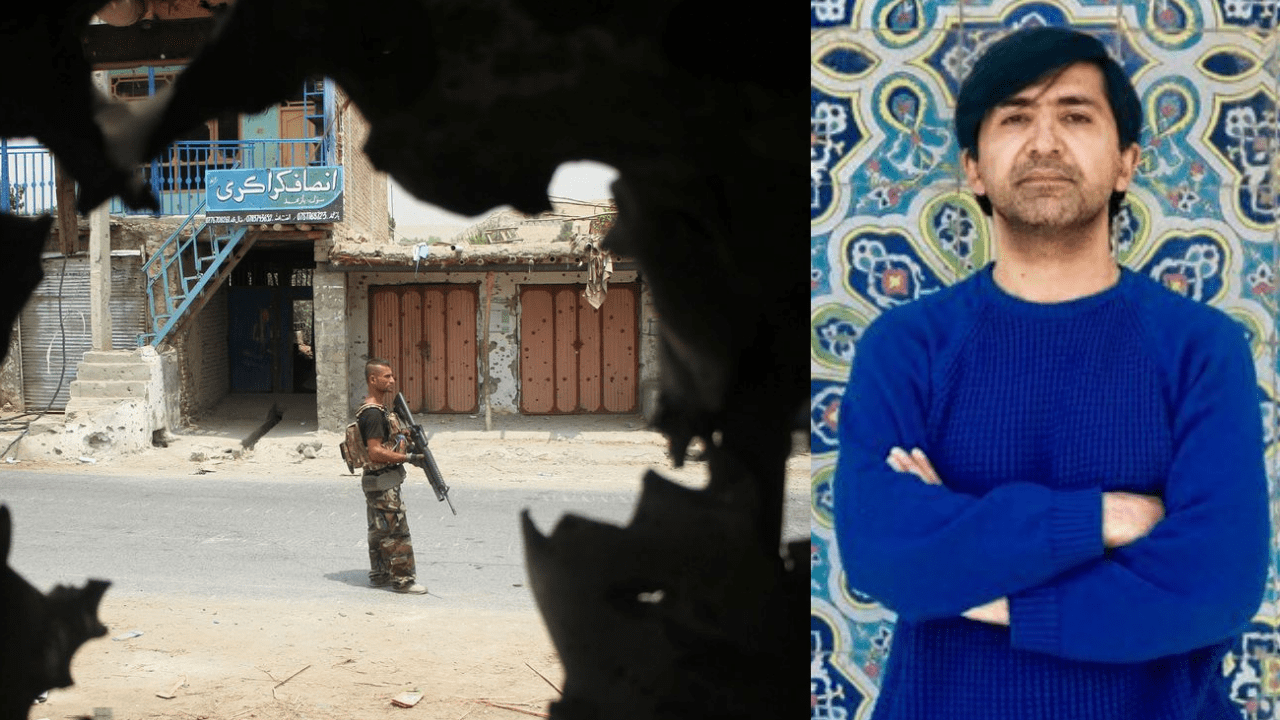

“I woke to gunshots in the night”: Fleeing Afghanistan | ticker VIEWS

Ticker Views

Market Watch: Greenland deals, Japan bonds & Australia jobs

Join David Scutt as we dissect fast-moving global markets and key insights from Greenland to Japan and Australia.

Ticker Views

Backlash over AI “Indigenous Host” sparks ethical debate

AI-generated “Indigenous host” sparks controversy, raising ethical concerns about representation and authenticity in social media.

Ticker Views

Business class battles and ultra long-haul flights with Simon Dean

Aviation expert Simon Dean shares insights on premium travel trends, business class, and the future of ultra-long-haul flights.

-

Ticker Views2 days ago

Ticker Views2 days agoDOJ to charge Don Lemon under historic KKK Act

-

Ticker Views22 hours ago

Ticker Views22 hours agoBacklash over AI “Indigenous Host” sparks ethical debate

-

Money3 days ago

Money3 days agoMarkets edge higher as 10-year yields hit new highs

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoOpenAI prepares first consumer device amid revenue boom

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoNASA’s Artemis II launch: Argentina joins first crewed moon mission in 50 years

-

Politics3 days ago

Politics3 days agoSupreme Court tariffs and Albanese approval drop: What you need to know

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoEU condemns Trump’s Greenland tariff threats: Trade tensions escalate

-

Ticker Views3 days ago

Ticker Views3 days agoWhy traditional flood warnings keep failing