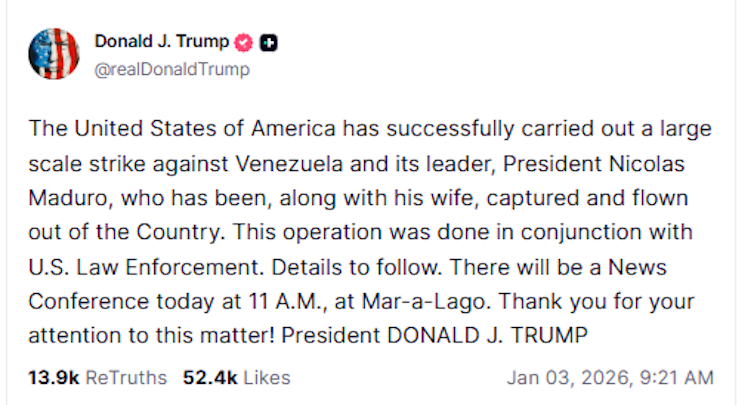

Venezuela’s president, Nicolás Maduro, has been apprehended and flown to the US where the US attorney-general has announced he will face charges of drug trafficking and narco-terrorism.

The US military’s operation to snatch Maduro was carried out in the early hours of January 3 and follows months of steadily mounting pressure on the Venezuelan government.

Now it appears that the US operation to remove a leader it has designated as a “narco-terrorist” has come to fruition. But whether the capture and removal of Maduro will lead to regime change in the oil-rich Latin American country remains unclear at present.

The US campaign against Venezuela is the product of two distinct policy impulses within the Trump administration. The first is the long held desire of many Republican hawks, including the US secretary of state, Marco Rubio, to force regime change in Caracas. They detest Venezuela’s socialist government and see overturning it as an opportunity to appeal to conservative Hispanic voters in the US.

The second impulse is more complex. Trump campaigned for election in 2024 on the idea that his administration would not become involved in foreign conflicts. But his administration claims that Venezuela’s government and military are involved in drug trafficking, which in Washington’s thinking makes them terrorist organisations that are harming the American people. As head of the country’s government, Maduro, according to the Trump administration’s logic is responsible for that.

During Trump’s first administration, his Department of Justice indicted Maduro on charges of “narco-terrorism”. Now Bondi says there might be a new indictment which also covers Maduro’s wife, who was taken into detention with him. The fact that US law enforcement was involved in their capture reinforces the idea that they will now face those charges in a New York court, despite an early claim by opposition sources in Venezuela that Maduro’s departure may have been negotiated with the US government.

What comes next?

The big question is what comes next in Venezuela, and whether either the Republican hawks or the “America first” crowd will get the outcome that they want: ongoing US military presence to “finish the job” or simply a show of US strength to punish its adversary which doesn’t involve a lengthy American involvement.

The US has discovered time and again in recent decades that it is extremely difficult to dictate the political futures of foreign countries with military force. The White House might want to see the emergence of a non-socialist government in Caracas, as well as one which cracks down on the drug trade. But simply removing Maduro and dropping some bombs is unlikely to achieve that goal after nearly three decades of bulding up the regime under Maduro and his predecessor Hugo Chavez.

The Trump administration could have learned this lesson from Libya, whose dictatorial government the US and its allies overthrew in 2011. The country collapsed into chaos soon after, inflicting widespread suffering on its own citizens and creating problems for its neighbours.

In the case of Venezuela, it is unlikely that American military’s strikes alone will be enough to fatally undermine its government. Maduro may be gone, but the vast majority of the country’s governmental and military apparatus remains intact. Power will likely pass to a new figure in the regime.

The White House may dream that popular protests will break out against the government following Maduro’s ousting. But history shows that people usually react to being bombed by a foreign power by rallying around the flag, not turning against their leaders.

Nor would Venezuela’s descent into chaos be likely to help the Trump administration achieve its goals. Conflict in Venezuela could generate new refugee flows which would eventually reach America’s southern border. The collapse of central government authority would be likely to create a more conducive environment for drug trafficking. Widespread internal violence and human rights violations could hardly be portrayed as a victory to the crucial conservative Hispanic voting bloc.

If the Trump administration dreams of establishing a stable, pro-American government in Caracas, it is going to have to do more than just arrest Maduro. Bringing about durable regime change typically involves occupying a country with ground troops and engaging in “nation building”. The US tried this with decidedly mixed results in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Trump has pledged to avoid such entanglements and Rubio has said that, for now at least, the US has no plans for further military action against Venezuela. Trump has a penchant for flashy, quick wins, particularly in foreign policy. He may hope to tout Maduro’s capture as a victory and move on to other matters.

Nation-building failures

In almost no recent US military intervention did the American government set out to engage in nation-building right from the beginning. The perceived need to shepherd a new government into existence has typically only come to be felt when the limits of what can be accomplished by military force alone become apparent.

The war in Afghanistan, for instance, started as a war of revenge for the terrorist attacks on the US on September 11 2001 before transforming into a 20-year nation-building commitment. In Iraq, the Bush administration thought that it could depose Saddam Hussein and leave within a few months. The US ended up staying for nearly a decade.

It’s hard to imagine Trump walking down the same path, if only because he has always portrayed nation-building as a waste of American lives and treasure. But that still leaves him with no plausible way to achieve the divergent political outcomes he, his supporters and America’s foreign policy establishment want with the tools that he has at his disposal.

Meanwhile the US president will face pressure from a range of constituencies from Republican hawks to conservative Hispanic voters to force wholesale regime change in Venezuela. How Trump responds to that pressure will determine the future course of US policy towards the country.![]()

![]()

Andrew Gawthorpe, Lecturer in History and International Studies, Leiden University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.